This helpful analysis conducted by the Wildlife Conservation Society brings to light new details of the positive developments coming out of Vietnam in regards to wildlife trade and preventing future pandemics.

Full Wildlife Conservation Society article below:

“HA NOI , VIET NAM | JULY 27, 2020

On July 23rd 2020 the Vietnamese Government released Prime Minister’s Directive No. 29 on urgent solutions to manage wildlife. This has been largely reported in the global media as a widespread ban on wildlife trade in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Wildlife Conservation Society welcomes the Prime Minister’s Directive and the renewed attention it will bring to combating illegal trade and consumption of wildlife. However, there are a number of points that have been mis-reported in the global media and areas we think require greater attention to reduce the risks of future zoonotic pathogen outbreaks:

1) The Directive does not ‘ban the wildlife trade’; rather it calls for heightened enforcement of existing laws on illegal wildlife trade in Vietnam.

Directive No. 29 does not introduce new restrictions on the trade and consumption of wild animals to reduce the risk of zoonotic pathogen transmission, as we have seen in China. Instead, it simply re-states the need to enforce existing legislation on wildlife protection. However, the Directive requests the courts and prosecutors to impose strict penalties on those who abuse their position and authority to commit wildlife crimes. This is the first time such corruption has been acknowledged and prioritized.

This Prime Minister and earlier ones have previously issued Directives calling for enhanced enforcement efforts on illegal wildlife trade (See Prime Minister’s Directive No. 3/CT-TTG 2014; and Prime Minister’s Directive No. 28/CT-TTG 2016). Whilst these often result in a flurry of action, this invariably fades. All these Directives have been unable to address the underlying causes of weak enforcement and ineffective prosecutions against wildlife criminals – for which additional legal reform is urgently needed. The major obstacles include corruption within the criminal justice system, and insufficient resources applied to fighting wildlife crimes in terms of budgets, manpower and technical capacity (e.g. financial investigations).

2) The Directive paves the way for future legal reform on wildlife consumption.

Directive No. 29 has not banned the consumption of wildlife; rather it has requested all relevant ministries to strictly monitor and control the acts of illegal wildlife consumption and review the current legal framework to propose amendments and supplementary regulations on the illegal consumption of wildlife. This is a positive development but requires specific time-frame, guidance, and specific government agencies to lead the process, without such it could take more than a year to finalise.

3) Measures proposed in the Directive to reduce the risk of zoonotic pathogen transmission in commercial wildlife farms are insufficient.

Directive No. 29 calls for an inspection of commercial wildlife farming across the country to ensure the legal origin of captive wildlife and safe conditions for human and captive wildlife, environmental sanitation and disease prevention. This is urgently needed as commercial wildlife farms are a high-risk interface for the transmission of zoonotic pathogens, as evidenced by viral surveillance in Vietnam over the last decade that has found multiple known and novel viruses in such farms. However, the inspection must be prioritized, time-bound, involve the relevant line agencies of the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and also representatives from international organizations such as FAO and WHO.

Given the significant risks that commercial wildlife farms currently pose, and the challenges of implementing effective disease prevention and and biosecurity practices, we believe an immediate temporary ban on issuing new permits for captive-raising of wild mammals and birds for commercial purposes should be put in place during the period that inspection, risk assessment and updated policies are formulated and implemented.

4) The Directive potentially weakens the existing ban on wildlife imports.

The Prime Minister issued a temporary ban on all wild animal imports on January 28th 2020 in Directive No. 5 on Prevention and Combating COVID-19. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) issued official guidance on February 6th 2020 stipulating that parts of wild animals processed into medicines, perfumes, watches and bags would be exempt from this ban. Directive No. 29 repeats the existing ban, however, adding additional exemptions. MARD should clarify as soon as possible the precise scope of these additional exemptions.

Conclusion

Whilst this Directive No. 29 is a positive development, it is not the game-changer that is being reported by some in the global media and that is urgently needed to prevent future zoonotic pathogen outbreaks such as that we are experiencing today. WCS will continue our work with partners in the Vietnamese Government, local academia and civil society, in addition to FAO and WHO representatives in Vietnam, on proposals to reform legislation to prohibit the commercial trade and consumption of wild birds and mammals, and ensure that enforcement and judicial agencies are fully mandated and resourced to enforce the law and bring wildlife criminals to justice.”

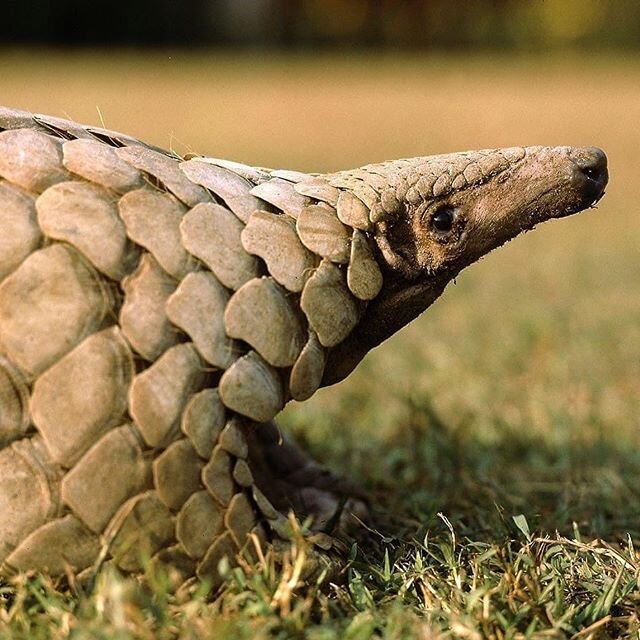

Photo © E & C Jacquet